Requests for Reviews and Legal support

Quick links

Introduction

We appreciate that in many circumstances an application for accommodation may be refused by a local authority, and sometimes without good reason. The individual may feel that this decision was unfair and should be challenged.

The process for challenging is not straightforward, but it should not discourage the individual from wanting to challenge. There are different ways in which an individual might be able to challenge a local authority’s decision, including:

- Internal review of a homelessness decision.

- The Council’s internal complaints procedure and complaints to the Ombudsman.

- County court appeal of a review decision.

- Judicial review of homelessness decisions.

When seeking to challenge a decision, the individual might have more than one option. The individual might also be able to get free and confidential advice from Civil Legal Advice as part of legal aid in England and Wales. The eligibility criteria for such legal aid is detailed on the UK Government Website.

1. Internal review of a homelessness decision

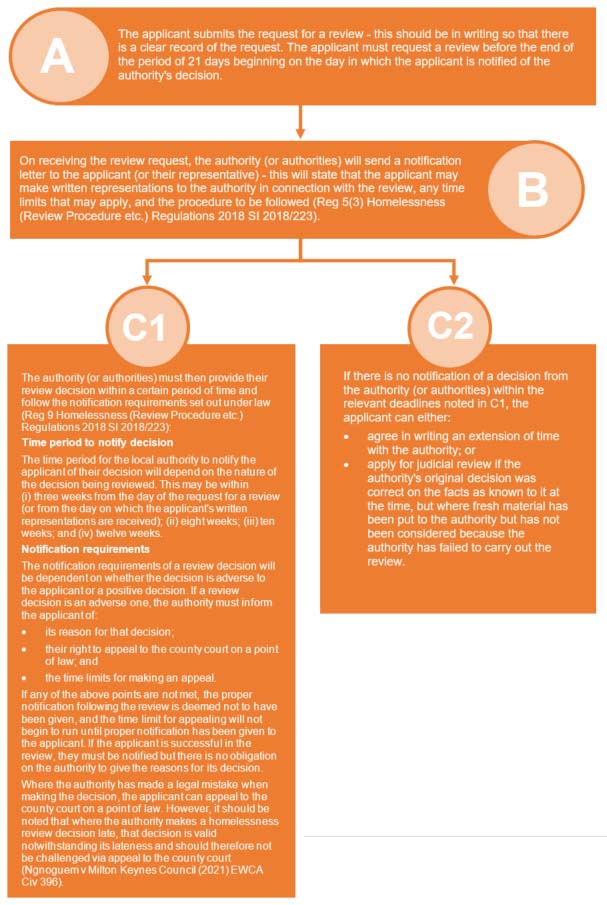

Most local authority decisions on homelessness can be challenged through an internal review under Section 202 Housing Act 1996. The review is carried out by the authority that made the decision and should follow a specific procedure.

There are a number of key local authority decisions that can be reviewed, including but not limited to the below:

- whether the applicant is eligible for assistance, homeless, in priority need, intentionally homeless or has a local connection, and therefore what duty the authority owes;

- a notification that an applicant has deliberately and unreasonably refused to cooperate with the authority;

- the suitability of accommodation provided (although this right does not extend to a review of the suitability of interim accommodation);

- whether a duty has been discharged towards the applicant.

It is important to note that the ability to request a review will be available whether the applicant either accepts or rejects the offer of accommodation. Therefore, even if an applicant considers that the accommodation is unsuitable, they should be encouraged to accept the offer but ask for a review if required.

Pursuant to Section 202(3) Housing Act 1996, the request for an internal review must be made within either:

- 21 days of being notified of the authority’s decision; or

- such longer period as the authority allows.

It should be noted that there is only a statutory right to one review of suitability. In addition, whilst a local authority must take into account the needs of the applicant in making a decision as to whether accommodation is suitable at the time of the offer, it is not required to set out its reasons in the letter offering accommodation as to why it considered that a property was suitable.

If an applicant misses the deadline for an internal review, they may still submit a request for an internal review together with a request to extend the time-period with details of reasons for the delay. If a local authority refuses to extend the time-period, an applicant can challenge this through a process known as “judicial review”. However, such decisions will be difficult to challenge unless it is shown that the local authority’s refusal to extend was unreasonable.

Some decisions are not subject to internal review, including, for example:

- a refusal to accept a homelessness application;

- a challenge based on the length of time in accommodation to be provided to people who are in priority need but intentionally homeless;

- the suitability of interim

There are various reasons why an applicant may wish to challenge the suitability of accommodation, including:

- the physical condition of the accommodation;

- the location;

- the affordability;

- overcrowding within the accommodation provided;

- risk of violence from any person.

Case example

An individual, who had dependent children and fled from domestic violence from their partner, challenged the suitability of accommodation offered to them by the council. The Court of Appeal upheld the challenge by the applicant – the property was in poor condition, had been vandalised and on visiting the area and the individual had been intimidated by youths. It was therefore found to be unsuitable.

In a scenario involving violence, an applicant’s refusal of accommodation may be based on their genuinely held subjective beliefs and the council should consider an applicant’s fear of future violence. However, if evidence available to the local authority would have allowed the authority to consider that those beliefs were not objectively reasonable, they are be entitled to find that the offer and acceptance of the property would have been reasonable.

In addition, the local authority must consider evidence about the risk of violence (e.g. police reports, relevant testimony, expert opinion) and the possibility that the incident of racial attacks in an area might be underreported. For example, an offer of accommodation to a Bangladeshi family in an area of active racial harassment was quashed because the authority had not had regard to the effect of under-reporting of racist attacks.

Case example

Temporary accommodation had been provided to the applicant and their family outside of a borough. As the applicant’s child suffered from a medical condition, the applicant requested to be rehoused within the borough in order to be closer to the child’s school, family and hospital. On conducting a review of the position that the current accommodation was suitable, the local authority upheld the original decision but had not considered whether other suitable accommodation existed closer to, or within, the district. On appeal to the County Court, the Court held that the local authority should have considered the availability of other accommodation.

In the event of a review, normally the accommodation must be suitable as the facts stand at the date of review – i.e. the local authority must reconsider the decision in light of all relevant circumstances at the date of the review, rather than only the facts at the time of the original decision.

However, in certain circumstances, the court may hold that in the interests of fairness the facts are to be considered at the date of the original decision – for example, when the applicant refused the original offer of accommodation on grounds of suitability.

Case example

The applicant, whose son had been born prematurely, was given temporary accommodation in a hotel. A few weeks later, the applicant was offered new temporary accommodation in an area different from that where the hospital was located, and where the infant son had further hospital appointments. The applicant refused the offer, and the local authority wrote to the applicant to discharge its duty to accommodate under section 193(3) and 193(5) Housing Act 1996. The discharge of duty was upheld on an internal review. However, the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal by the applicant, and in doing so, somewhat established the principle for any review under Housing Act 1996 that the ‘cut-off date’ for what facts should be properly considered by the local authority depends on what is being reviewed:

- Where the review is effectively a continuation of the decision-making process, the facts continue to be relevant up to the date of the review – for example, a review of suitability requested by an applicant who had at the same time accepted the accommodation and is in occupation of the accommodation.

- Where the decision is a final one, no facts relating to a point after that date will be relevant to the review.

Case example

2. The Council's internal complaints procedure and complaints to the Ombudsman

If a review of a decision is not favourable to the applicant, a complaint can be raised with that local authority/council. The procedure for making a complaint should be detailed on each council’s website. Each council will have its own internal complaints procedure, which usually, will be composed of separate stages. When the investigation is complete, the council will write to the applicant to explain their final decision and the reasons for it.

If an applicant is dissatisfied with the council’s final response to a complaint, or a final response hasn’t been received within 12 weeks of the original complaint, then a complaint can be made to the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman who can investigate complaints about the way in which a decision has been made. The Ombudsman is independent and will examine the case from both sides to recommend a decision they think is fair. Where there is a right of review, and/or a complaints procedure within the housing authority, the Ombudsman would expect the individual to pursue their rights through these arrangements before making a complaint. An Ombudsman will not usually look at a case if it has been more than a year since the applicant received a final response from the council.

If there is any doubt about whether the Ombudsman can look into a complaint, the individual should seek advice from the Ombudsman’s office. The complaint form to be used when making a complaint can be located on the Ombudsman’s website. The complaint procedure to the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman is set out on its website.

It should be noted that the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman considers complaints about the council services generally, including homeless and waiting list applications, and the administration of housing benefits. This is not to be confused with the Housing Ombudsman, which considers complaints from council tenants and leaseholders about the council’s service as a landlord.

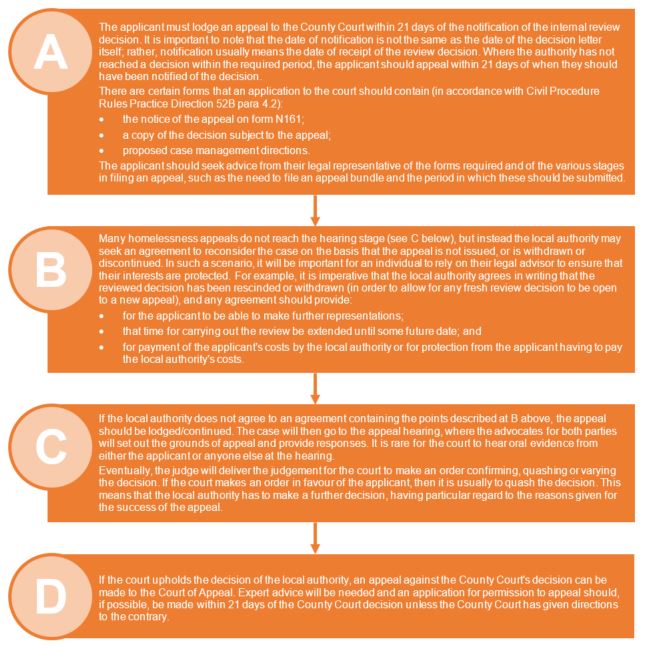

3. County Court appeal of a review decision

If the individual remains dissatisfied with an adverse review decision made by the local authority, or they did not receive notification of that decision within the appropriate time, an appeal can be made to the County Court (Section 204(1) Housing Act 1996).

An appeal can generally only be brought on a point of law, and not on the facts of the case. This means that the County Court does not usually consider the facts but only ensures that the local authority has correctly understood and applied the law, and followed a fair decision-making process.

The individual should be referred to a solicitor when deciding to make an appeal. The legal advisor will be able to:

- establish the relevant time limit (i.e. an applicant must lodge an appeal to the County Court within 21 days of the notification of the review decision (Section 204(2) Housing Act 1996));

- establish whether the case has legal merit (whether there is a point of law);

- work out whether the individual is entitled to public funding, and if so;

- refer them to a solicitor who can take the case on.

Before making an appeal, it is appropriate (if time allows) for the applicant to write a letter to the local authority outlining the basis of the appeal. The letter should also invite the local authority to rescind its decision on review and set a time limit for a fresh review to be carried out.

In deciding whether a case has legal merit, the starting point for the County Court will be the local authority’s decision letter. This is because the local authority alone is responsible for deciding the facts. The focus will be on whether the local authority has properly applied the law to the facts that it has found, and whether it has considered all relevant matters. Reasons for a County Court appeal on a point of law would include:

- the decision is beyond what is lawful;

- the decision goes beyond what is within the council’s remit;

- the decision is perverse or irrational;

- the decision is in breach of natural justice;

- the decision involves bias or bad faith;

- the local authority failed to make appropriate enquiries;

- there was no evidence to support any factual findings;

- the local authority failed to take into account relevant factors/took into account irrelevant factors; and

- the local authority provided inadequate reasons for their internal review decision.

Overview of the County Court appeal procedure

4. Judicial review of homelessness decisions

There are some homelessness decisions where an individual will not have a right to request a review of a decision by the local authority. The only way to challenge these decisions is by way of judicial review in the High Court. These include where a local authority:

- refuses to accept a homeless application, including a reapplication on different facts;

- breaches the Public Sector Equality Duty when carrying out inquiries;

- fails to carry out an assessment of the applicant’s needs or provide a personalised housing plan;

- includes unreasonable steps in a personalised housing plan;

- fails to commence taking steps to prevent homelessness or relieve homelessness;

- operates a blanket policy not to use its power to secure accommodation to prevent or relieve homelessness;

- refuses to provide accommodation pending review or appeal to the County Court;

- refuses to provide interim accommodation or provides unsuitable interim accommodation;

- accommodates someone who is pregnant or has dependent children in a bed and breakfast for longer than six weeks where no exception applies;

- evicts an applicant from interim accommodation without reasonable notice;

- decides to refer to another authority at the relief stage, or chooses not to make a referral at any stage; or

- refuses to make a fresh decision on suitability following a change in circumstances.

It is important to note that judicial review is not available where a person has an alternative remedy available (e.g., an internal review or appeal in the County Court) or simply because they have missed the time limit to bring an appeal.

Whilst the suitability of accommodation can be challenged by judicial review, it should be noted that this is only in relation to interim accommodation. Judicial review can also be brought where the court refuses to make a fresh decision on suitability when given details of a significant and material change of circumstances.

Case example

The applicant, who was the mother of three children, was granted temporary accommodation whilst the local authority determined whether or not it owed the applicant full housing duty. The temporary accommodation had multiple issues, including damp and mould, lack of facilities and was far away from the children’s schools. The applicant chose to leave the temporary accommodation provided to her, which led to the council’s decision that their duty had been discharged, as the applicant had made herself intentionally homeless. There were three grounds of appeal that the County Court considered in this case:

- one of the children suffered from eczema, and the appellant argued that the mould and damp was detrimental to the child’s condition. The court found that the mould and damp were not serious enough to be material to the issue of suitability, and that the condition could be treated without the facilities missing from the accommodation.

- the appellant argued that the local authority had wrongly created a category of temporary accommodation and, in doing so, applied a lesser standard to the question of suitability. The Court held that it was relevant to consider the amount of time for which the accommodation was to be made available.

- the appellant also argued that the accommodation was too far from the school, a journey that would involve the appellant and her youngest child making the same, long journey four times a day. On this point, the Court held that the local authority had failed its duty under s.11 Children Act 2004 to have regard to the need to safeguard and promote the welfare of the children.

In considering the above case example, it should be remembered that whilst the standard of suitability of accommodation is not lower for temporary accommodation, the local authority can take into consideration the amount of time that will be spent in the accommodation in determining its suitability.

Furthermore, local authorities have a great deal of discretion in determining suitability. The below case examples demonstrate where an applicant was successful and where another applicant was unsuccessful when challenging the suitability of interim accommodation by judicial review. The drawbacks of the interim accommodation offered must be serious enough to render the accommodation unsuitable for the purposes of the interim period. A judicial review is likely to hinge on what actions the authority took to establish that the accommodation was suitable and whether they have considered any relevant evidence offered.

Case examples

Overview of the judicial review procedure